Origins at a Cultural Crossroads

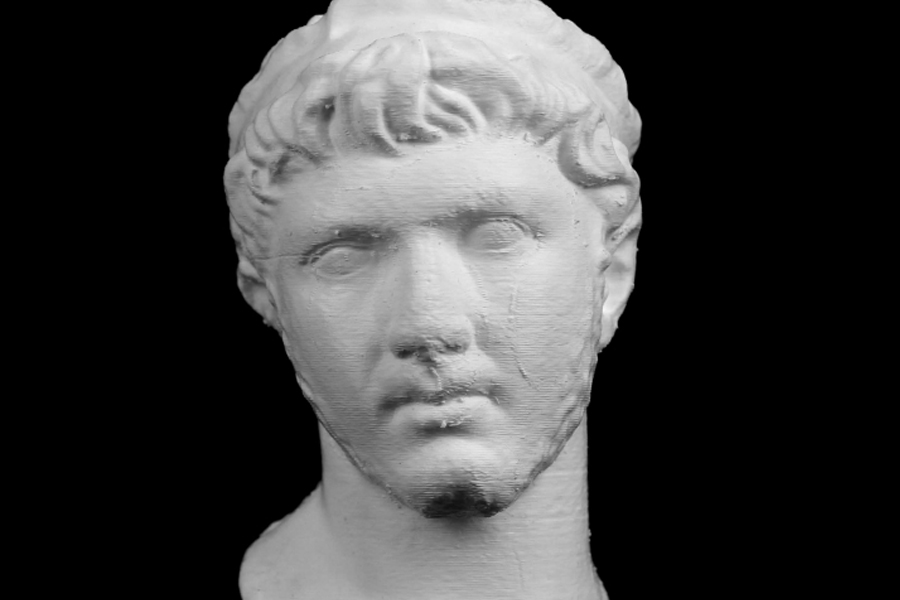

I picture Ptolemy Of Mauretania arriving in history like a bright tessera in a sprawling mosaic. Born around 13 to 9 BC in Caesarea, today’s Cherchell on the Algerian coast, he stood at a confluence of legacies. His father, Juba II, was a Berber king raised in Rome after civil war toppled Numidia. His mother, Cleopatra Selene II, was the daughter of Cleopatra VII and Mark Antony, a living thread pulled from the tapestry of Ptolemaic Egypt. The name Ptolemy was no accident. It was an intentional flare sent across time, signaling the survival of a Hellenistic lineage inside a Roman world.

When Cleopatra Selene died around 5 BC, Ptolemy was still a child. He left the sunlit porticoes of Caesarea for the marbles of Rome, entering the household of Antonia Minor, an aunt nestled close to the Julio-Claudian center of power. There he learned Latin and Greek, courtly manners, and the delicate art of serving an empire without becoming its slave. He returned to Mauretania a polished prince, a man cut to Caesar’s pattern but stitched with African thread.

A Kingdom Between Sand and Sea

Mauretania sprawled like a wide cloak along the Atlantic and Mediterranean, a land of orchards, purple dye workshops, and ports thrumming with trade. Juba II had already turned Caesarea into a cultural beacon, a North African echo of Alexandria with libraries, statuary, and scholarship. By around 20 CE, Ptolemy joined his father on the throne as co-ruler. Their coinage announced it, placing father and son side by side for all to see.

Ptolemy inherited the crown entire in 23 CE. He ruled on a Roman leash like other client kings. However, the leash allowed him to move. He protected borders, facilitated trade, and formed alliances. Murex purple, garum fish sauce, lumber, and grain exports boosted the kingdom’s wealth. My merchant-minded Ptolemy would sniff barrel brine and hear coins clank in amphora-darkened warehouses in his metropolis.

War, Honors, and the Tacfarinas Revolt

The desert, however, has a way of pushing back. For years, the Berber rebel Tacfarinas harried Roman frontiers and stirred unrest among local tribes. Ptolemy fought him as both king and Roman ally. In 24 CE, with support from the Roman proconsul Publius Cornelius Dolabella, Tacfarinas was trapped and killed, his uprising snapped at last.

Tiberius rewarded Ptolemy with triumphal honors. An ivory scepter. A richly embroidered robe. The cherished title king, ally, and friend. It was Rome’s way of applauding without ceding too much greatness. His reputation as a capable ruler spread, even as Roman writers could not resist the familiar note of condescension. Tacitus painted him as indolent and fond of luxury. The cloak sat heavy and bright on Ptolemy’s shoulders, admired at home and whispered about in Rome.

Family Portraits: The House of Juba and Cleopatra

The family at the heart of this story reads like a cast list drawn from different stages on the Mediterranean.

- Juba II, the father: A scholar-king and builder, educated in Rome after his own father, Juba I, fell on the wrong side of Caesar’s triumph. He wrote books on history and geography, minted coins that conversed with Greek traditions, and filled Caesarea with the monuments of an urbane monarch.

- Cleopatra Selene II, the mother: Heir to the Ptolemaic dream and Cleopatra VII’s daughter. Her marriage to Juba II blended dynasties and geographies. She rests in the Royal Mausoleum of Mauretania, the grand tomb that still broods above the coast.

- Drusilla of Mauretania the Elder, the sister: A faint silhouette in the sources, named in the Roman fashion and likely reaching adulthood, though her path fades into the fog of unwritten lives.

- Julia Urania, the spouse: A queen consort who likely came from Emesa in Syria. Her name survives on a funerary inscription set up by her freedwoman. The marriage, formed in the late 30s CE, carried eastern connections into the Mauretanian court.

- Drusilla of Mauretania the Younger, the daughter: Born around 38 CE, raised in Rome after Ptolemy’s death, married first to the Roman procurator Marcus Antonius Felix and possibly later to Sohaemus of Emesa. Through her, the family’s thread may have run into Syrian royalty, with a likely son, Gaius Julius Alexion, and perhaps further descendants in the Emesene line.

Behind them stood formidable ancestors: Cleopatra VII and Mark Antony, Ptolemy XII Auletes, Hiempsal II of Numidia, and the shadows of Roman patricians like Marcus Antonius Creticus. Ptolemy’s household was a corridor of portraits in different styles, each face turned toward a different capital.

Coins, Cults, and Civic Patronage

I have always loved how coins talk. Ptolemy’s coinage spoke of continuity and balance. Early issues showed the shared sovereignty of father and son. Later, in 39 CE, Ptolemy minted gold that paired his own image with his father shown in pharaonic style, a deliberate gesture tying Mauretania to an Egyptian past and a broader Hellenistic world.

At home, Ptolemy sponsored temples in Caesarea, including those honoring Saturn Frugifer, a god of fruitfulness whose worship fit a land of orchards and grain. His father was honored in royal cult, a practice later criticized by Christian writers but rooted in ancient norms of kingship. Abroad, Ptolemy sprinkled favors. Athens set statues for him and his family. The Lycian federation saluted him. In Spain, he served civic roles in places like Gades and Carthago Nova. These were not random gestures. They were lines in a ledger of prestige, gifts traded for status and security.

The Cloak, the Summons, and the End

In the winter of 39 to 40 CE, Ptolemy was summoned to Caligula’s court. The scene feels theatrical to me, a man resplendent in purple stepping onto a stage where the script changes without warning. Ancient writers give different reasons for what happened next. Suetonius says the crowd admired Ptolemy’s cloak, and Caligula’s jealousy flared. Cassius Dio suggests envy of wealth. Modern interpretations point to politics, to the emperor’s growing paranoia, perhaps to fears of plots linked to men like Lentulus Gaetulicus or to Caligula’s own sisters.

Whatever the motive, the order came down. Ptolemy was executed. A client king, cousin to emperors, last male scion of the Ptolemies, cut off miles from home. Rome applauds and Rome devours. In Mauretania, his freedman Aedemon led a revolt in response, fierce and doomed. By 44 CE, Claudius had annexed the kingdom, dividing it into Mauretania Tingitana in the west and Mauretania Caesariensis in the east. The crown became a provincial insignia, the purple cloak folded into Roman administration.

Why This Story Resonates

I keep returning to Ptolemy because he is a tide line where worlds meet. Berber kingship, Greek dynastic dream, Roman law, and empire. His rule shows how a client king could be both empowered and helpless, a partner and a hostage. His coin portraits smile with serene assurance, yet his life arcs toward a door that opened in Rome and did not let him step back out.

FAQ

Was Ptolemy Of Mauretania a Roman citizen?

He lived as a Roman insider, raised in the household of Antonia Minor and recognized formally as king, ally, and friend of the Roman people. Client kings like Ptolemy commonly held Roman citizenship or its privileges, and he moved within imperial circles as one of their own.

Did Ptolemy rule Egypt like his Ptolemaic ancestors?

No. He ruled Mauretania in North Africa. His mother’s Ptolemaic lineage gave him prestige and a powerful name, but Egypt had been annexed by Rome decades earlier.

How wealthy was he?

No modern net worth applies, but he governed a prosperous kingdom. Mauretania exported purple dye from murex, garum, timber, and agricultural products. Ptolemy’s court minted gold coins and displayed luxuries that impressed and irritated Roman observers.

What happened to Mauretania after his death?

It erupted in revolt under his freedman Aedemon, then was subdued by Roman legions. In 44 CE, Claudius annexed the realm and split it into provinces called Mauretania Tingitana and Mauretania Caesariensis.

Is Ptolemy really related to Cleopatra VII?

Yes. His mother, Cleopatra Selene II, was the daughter of Cleopatra VII and Mark Antony, making Ptolemy a direct descendant of the Ptolemaic dynasty through his maternal line.

Who was Tacfarinas, and why was that war important?

Tacfarinas was a Berber leader and former Roman auxiliary who waged a prolonged guerrilla conflict against Roman authority in North Africa. Ptolemy’s role in the final defeat of Tacfarinas in 24 CE earned him triumphal honors from Tiberius and reinforced his value as a Roman ally.

Where is Ptolemy buried?

His burial place is not securely known. His mother rests in the Royal Mausoleum of Mauretania near Tipasa. Ptolemy was executed far from home, and no confirmed tomb has been identified.

Did Ptolemy have a son?

No confirmed sons are recorded. He had a daughter, Drusilla of Mauretania the Younger. Through her marriages, likely including one to Sohaemus of Emesa, a son named Gaius Julius Alexion may have continued the line in Syria.

What languages did Ptolemy speak?

He would have been fluent in Greek and Latin due to his education and political role. His heritage was Berber, and his court sat within a multilingual world tied to Africa and the Mediterranean.

Why did Caligula execute him?

Ancient sources disagree. Some point to jealousy sparked by Ptolemy’s luxurious purple cloak or his wealth. Others see political anxiety and suspected conspiracies at a time when Caligula feared rivals. What is clear is that his execution was abrupt and without public trial, a stark reminder of imperial whimsy.